Walter Sickert: The Avant Gardiste

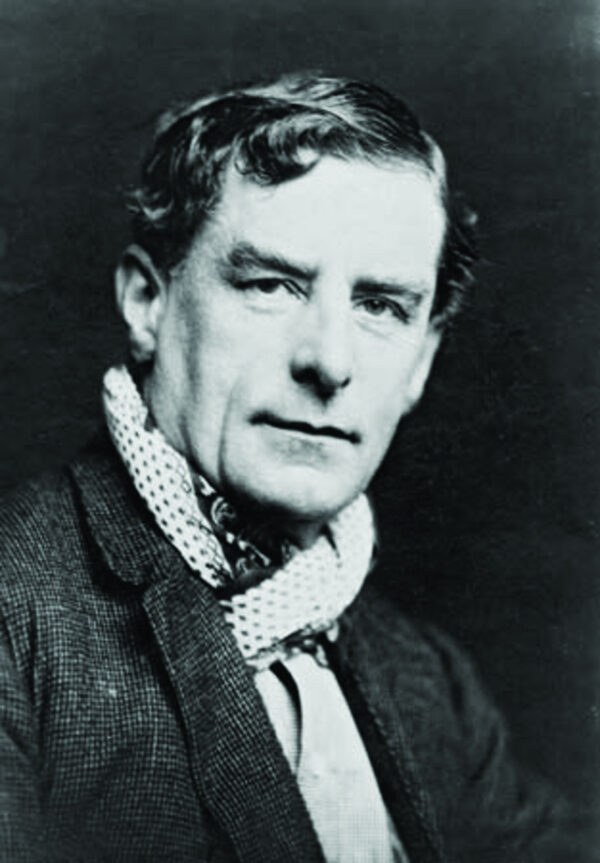

Contemporary British artist and Royal Academician, Jock McFadyen looks at the life of the German-born British painter and printmaker who was a member of the Camden Town Group of Post-Impressionist artists

By Jock McFadyen

October 17 2024

The British painter Walter Sickert was born in Munich in 1860 into a rapidly changing world. His family moved to England when he was eight years old and his life spanned a period which saw the invention of the motor car, the aeroplane, the machine gun and the tank, as well as the first world war and the first two years of the second. Photography, radio and cinema signalled the first stirrings of the age of media. The medium was not yet the message but by the time Sickert died in London in 1942 the Sixties of Marshall McLuhan, Andy Warhol and the Beatles was only twenty years away.

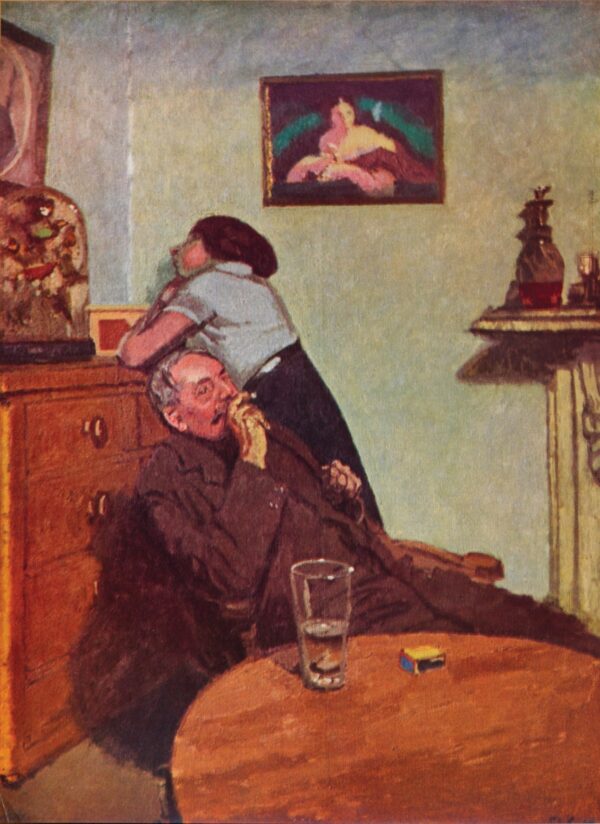

Sickert loved the theatre and had himself been an actor. He was a man about town and a dandy who certainly wasn’t going to let the new century leave him in the weeds. His use of photography in the pictures of the 1930s was a way of ensuring that his paintings kept abreast of the astonishing speed of the new world of inventions and images which was evolving before his eyes. And with the aid of news photographs he gave us paintings of Amelia Earhart, King Edward VIII and Edward G Robinson among others, without any of them having to sit down and keep still in front of him. Earlier in the century, the artist’s disquieting series of Camden Town nudes that were painted between 1905 and 1913 shocked the Edwardians; the pictures referenced newspaper items of the day against the backdrop of the recently invented railway system, which transformed the ‘new town’ of Camden.

Dr Crippen was the first murderer to be apprehended by radio telegraph, mid-Atlantic, as he tried to evade capture for the murder (and acid bath disposal) of (most of) his wife at number 39 Hilldrop Crescent in Holloway. Sickert took great interest in the reports of this case and it is generally reckoned that the sensation influenced his work at that time. This connection even convinced the American crime writer Patricia Cornwell that Sickert himself was Jack the Ripper. That aside, the fact remains that Sickert’s work of these years anticipates the quintessentially English ‘Kitchen Sink’ painters who emerged in the 1950s as well as artists like LS Lowry. Another painter of glum things, Lowry was a late starter who was taught in Manchester by the French artist Adolphe Vallette.

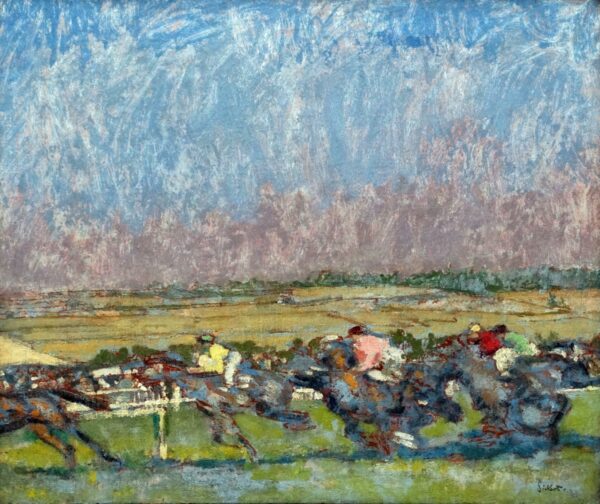

And let’s not forget Modernism. That great 19th-century idea about the 20th century that urged art forward to keep pace with things and stay awake. Modernism concerned itself with the form and style of pictures rather than content or subject. Avant-Garde is a French expression and English painters were in thrall to Paris and the French when it came to art in the inter-war years. But Sickert was a contrarian, a Stuckist even, and he had been trained by that other great contrarian, James Abbott McNeill Whistler. He was never a joiner and, like Lowry after him, was influenced by an older French painter. In Sickert’s case, it was Edgar Degas who informed the painterly realism of the younger artist and thereafter he stuck with his primary influences of Degas, Whistler and miserabilism. Degas in the rain. He even went on to claim that he painted in the English style for the French Market. Confusingly though, Sickert’s work is not inconsistent with the ferment of 20th-century Modernism because in fact it is the paint itself that is Sickert’s subject matter, and it is under his touch that paint comes alive. And when the paint is alive, the scenario is also alive and the viewer sits up and takes notice. Perhaps his theatrical background and love of the stage prompted his sense of purpose to focus on the creation of arresting images.

Beyond painting, art and Modernism however, it’s Sickert’s reach (in today’s parlance) for which he will be remembered. And the variety of media where ‘Sickertian’ elements exist suggests a significance of even greater import than that of the cloistered world of fine art. Just as he sought popular subjects from newspapers and the wireless, it’s not beyond reason that these media might in turn have absorbed something of Sickert. He was, of course, an important plank in the unfolding story of British painting and his friendship with the ageing Degas certainly helped to form a bridge between British and French art, but the muted palette and focus on mundane subjects, as well as a particular kind of singular narrative frankness, can be found in British cinema, theatre, television and pop music to this day, and Sickert is surely at least one of the reasons for this.

Coronation Street is pure Sickert. The lamenting trumpet and wet grey tiles of the intro could easily be replaced by ‘Penny Lane’ or ‘Eleanor Rigby’ by The Beatles. From John Osborne’s 1956 Look Back in Anger all the way to the Sex Pistols’ Never Mind The Bollocks of 1977, there is a kernel of what Sickert was on about, and when funding for John Mackenzie’s 1980 film The Long Good Friday was only forthcoming if the movie was overdubbed in American-ese, it was a Beatle who stepped in to ensure that Bob Hoskins’s gangster could eff and blind in authentic and recognisable Cockney.

David Storey’s This Sporting Life of 1963 and Karel Reiz’s Saturday night and Sunday Morning of 1960 continue the line, as do the films of Ken Loach and Mike Leigh, and the photographs of Tony Ray-Jones and Martin Parr are in there too along with all the other imagists and storytellers of ordinary things that nestle in Sickert’s legacy. He was a great British painter who was born in Germany of a Danish father and an Anglo-Irish mother and had the audacity to export his Englishness to France, while his painter contemporaries dreamed of all things French. Some years ago, I was invited to introduce and present a film of my choice at the Royal Academy and I chose Tony Hancock’s 1958 comic masterpiece and pastiche of the art world, The Rebel. A few weeks ago, I was invited to write a thousand words for this 35th anniversary issue of Boisdale Life magazine. But a picture is worth a thousand words. I think that goes for movies too, and the Hancock movie makes the case above far better than I ever could. You’ll be happy to know you can watch it on YouTube...