Lots of Reasons To Be Cheerful

The doomsters and gloomsters have it wrong, says Sebastian Payne — there is much to celebrate about our ever-adaptable political system

By Sebastian Payne

October 7 2024

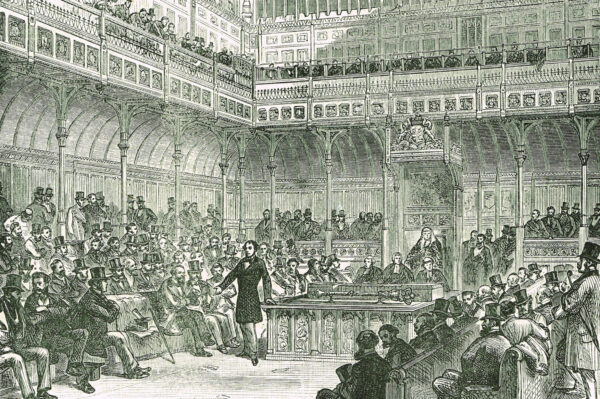

Bashing Britain’s politicians is sadly par for the course. After the turmoil of the Brexit years, four Prime Ministers, and three general elections in short order, is it surprising that our faith in elected MPs and ministers has slumped to a four-decade low? Indeed, according to pollsters Ipsos MORI, just 9% of the British people say they trust our politicians. Yes, it’s true that, like all Western democracies, Britain’s political system has gone through one or two major convulsions. But what we have seen time and again in recent decades is that the system works because it manages to adapt. When the public has been unhappy, something in the system changes. When politicians don’t adhere to their wishes, something budges. When a Prime Minister is not up to the job, they are gone. There is also provision for pressure valves. Take the Brexit vote. Britain is one of the few European countries not to experience the rise of a far right force: as I write, Marine Le Pen humbled Macron in the EU elections. In Germany, there is Alternative for Deutschland; and the Netherlands has given Europe Geert Wilders. The UK is not alone in facing acute pressures: rising concerns about the levels of immigration; fears over borders and security; a wider sense that the political elites have lost touch with the concerns of many. But whereas other countries have sprouted radical figures within their legislatures, the UK had the safety valve of the referendum. But what there is to celebrate about Britain’s political culture goes beyond the mechanisms and successes of the last decade. Our parliament is one the oldest legislatures in the world, renowned for its stability and continuity throughout many centuries. The Westminster system has been exported successfully across the globe, flourishing in numerous Commonwealth nations from Canada to New Zealand.

Although the House of Lords itself is in dire need of reform and modernising, it still acts as an effective cooling saucer to the hot tea of the Commons. Our first-past-the-post electoral system ensures that our parliament accurately reflects the voting desires of the country, ensuring that the broad will of the people is reflected in its MPs. It has also curbed extreme opinions and ensures that our politicians are anchored in their demographically diverse constituencies. And in an age when people feel cowed and must temper what they say, our parliament remains a crucible for free speech. As we’ve seen with the devolved assemblies, designing a chamber to be more consensual does not yield better debates or stronger governance. We should celebrate that at the most critical national inflection points — Theresa May’s failed Brexit deals, Boris Johnson’s more successful ones, or the Rwanda legislation — the House of Commons is undoubtedly the cockpit of the nation. While some decry the ya-boo thrust of Prime Minister’s Questions each week, it remains the most essential political temperature check. Few other political systems have such a regular opportunity to test their leaders in such a public manner. It is not only the performance of the individual that is judged, but how they sit within the party. Do their MPs offer fulsome support, or are they more muted? Do the jokes land well, or are they stilted? Do their arguments win the day, or are they swatted away easily by the opposition leader?

Plus, there is one more hidden, but crucial, element to PMQs. From Tuesday afternoon onwards, the Prime Minister gathers with his core team to plot out the attack and defensive lines of questioning. In the midst of f iguring these out, the whole Whitehall machine clicks into gear to find the answers — officials scurrying away across departments to give Number 10 what it needs. Often in the process of doing this, problems and flaws are discovered, weeded out and fixed. Few other nations do this at such frequent intervals. And it’s not just Westminster we should be proud of. Britain is one of the most overly centralised developed economies, yet our political system is adapting with the rise of directly elected mayors. Much of England has a powerful executive figure for their conurbation or part of the country who can deliver real change as the champion for their area. From Andy Burnham in Manchester to Ben Houchen in Teesside, some of the most exciting, stimulating British politicians of our time are found outside the capital. This new development has seamlessly entered our political system.

So there you have it — some reasons to be cheerful and proud of Britain’s politics and political system. It’s obviously far from perfect — we have some big questions to answer, not least how to unlock the growth conundrum and we still need to improve our productivity. We need to build more houses in the right places, where people want them. We need to increase our defence capabilities to confront the grave dangers we face around the world. But compared to other Western democracies, our system is not only working well but thriving, even if there is still much more to do.

Sebastian Payne is Director of Onward, the centre-right think tank .