Flora Macdonald: Pretty and Bold

Bruce Anderson reminds us of the role played by the Scottish heroine in the aftermath of the Battle of Culloden

By Bruce Anderson

July 4 2023

This is a tale of heroism and tragedy, of romance and chivalry, but also of cruelty and suffering. It deals with the final destruction of an ancient order, in which a proud way of life was overwhelmed and passed from the front pages of history to mythology and legend.

No proper Scotsman can hear ‘The Flooers o’ the Forest’, a lament that commemorates the noblemen and other paladins who fell at Flodden, without moist eyes and deep emotion. With Pretty Young Rebel: The Life of Flora Macdonald, author Flora Fraser has produced another lament, for the ‘flooers’ of the glens, the mountains, the moorland and the rough seas.

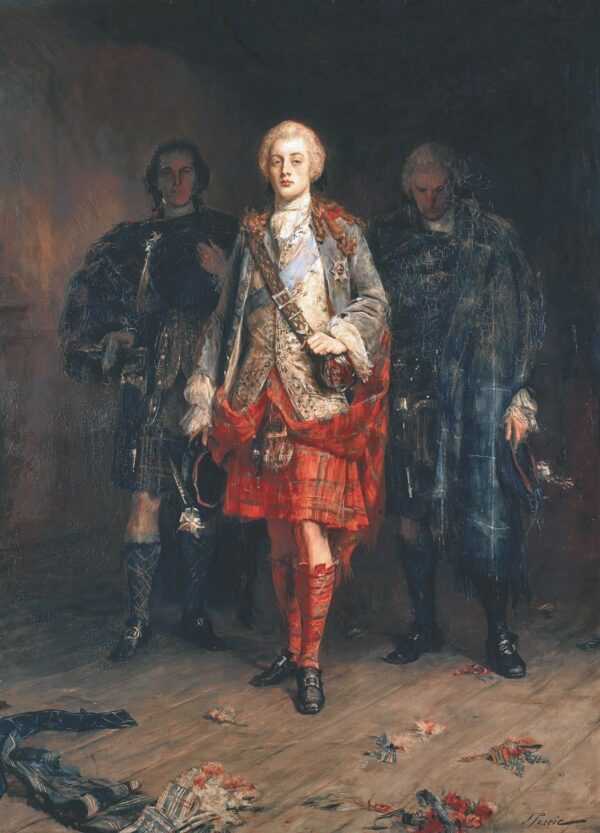

The story is dominated by two romantic figures: Prince Charles Edward Stuart, the Young Pretender, and Flora Macdonald, his rescuer. The young Bonny Prince Charlie appeared to have many qualities. He found it easy to inspire his followers and he looked like a king. But he was too late. In 1714, after Queen Anne’s death, the Crown passed to George I, as had been ordained by Parliament in the Act of Settlement, to ensure a Protestant Succession.

But there were a number of problems. First, Parliament might have declared for the Hanoverians, but many of his new subjects – even Protestant ones – were uneasy. They thought that the Crown should descend from Divine ordination, not an Act of Parliament. Such thoughts led to an inescapable conclusion: that the rightful King of Great Britain was the Old Pretender, James Francis Edward Stuart, Charles’s father.

To make matters more awkward, George I was only 54th in line to the throne. His claim to the throne descended from another romantic figure, the Winter Queen, Elizabeth of Bohemia, a daughter of James VI of Scotland and I of England. Charles I also had a daughter, however, nearer to the throne than her Aunt Elizabeth and thus taking precedence. She and her descendants were enthusiastic breeders. Ultimately, George I was emphatically not a romantic figure. One anti-Hanoverian ballad described him as “The wee German lairdie”. No divinity hedged that King; he did not even speak English. This did not deter the Whigs, who were to enjoy a 50-year hegemony, including the long Premiership of Robert Walpole. They were happy with a dull monarch, under whom the often bloody constitutional conflicts of the 17th century could gradually abate. Stolid Germans called George promoted the growth of political stability in England in a way that Romantic Stuarts could not have emulated.

Yet there were early chances of a Stuart revival. In 1715, before George I had got his feet properly under the throne, a Jacobite rising broke out, followed by a second attempt in 1719 (‘Jacobite’ after James, the Old Pretender, an unimpressive figure), but both of those forays were ill-led at the highest level, and half-hearted in execution. In the meantime, England gradually settled down and accustomed itself to dullness and stability.

Yet the Highlands were different, especially in the Outer Hebrides. Known as the Long Island in the 18th century, this was actually a chain of islands, stretching from Barra to Lewis. As Fraser points out, these are “remote and wind- lashed maritime lands. A strand of rough diamonds, they lie off the west coast of mainland Scotland in the Atlantic Ocean on the outer edge of Europe. The ground, at the mercy of the ebb and flow of the ocean and washed by driving rain much of the year, can appear more water than land”.

It is easy to see why the earlier Kings of Scotland, comfortably ensconced in Edinburgh, took little interest in these farthest-flung extremities of their domains. They left the government in the hands of local clan chiefs, principally Macdonalds and MacLeods. The bleak conditions bred two attributes: loyalty and hardiness. A good chief could command the allegiance of his followers. Brought up for warfare, they were formidable soldiers.

Even so, the Long Island was far more than a primitive society peopled by warriors living at subsistence level. There was a high level of literacy, and although the chiefs usually spoke Gaelic to their followers, they were not only proficient in English, but often also in French and had a good grasp of Latin. In the midst of rude nature, high culture flourished. This was an ethos which bred self-confidence among its leaders. The chiefs knew that there was a King above them, but he was a long way off and there was a strong consciousness that they themselves were of royal descent from the early Dark Ages over 500 years before William invaded England in 1066.

Subsequently, the third son of a minor Norman nobleman travelled to Scotland and his progeny later became stewards of the Scottish Royal household. After a generation or two, they styled themselves after as Stewarts and ultimately became Stuarts – and Kings – after marrying into Robert the Bruce’s line.

This recent lineage was not significantly impressive to clan chiefs who could trace a far more distinguished genealogy. To the clansmen themselves, the chief was still a sort of king, and there was a further factor: In large parts of remoter Highlands, the Reformation had not penetrated. Roman Catholicism still prevailed.

Then came Bonnie Prince Charlie who, in 1745, chose an opportune moment. Britain was at war with France, so the UK was thinly garrisoned at home. Although the Prince arrived with only seven followers, he quickly persuaded several clan chiefs to rally to his cause at Glenfinnan, in the heart of Clanranald country, and then marched on Edinburgh, a triumphant entry sealed by a victory at the Battle of Prestonpans.

His charisma seemed to be sweeping all before him. Flora Fraser describes one observer’s reaction. He acknowledged spectators “with an air of grandeur and affability ... In all my life, I never saw so noble nor so graceful an appearance as His Highness made”.

Appearance is the key word. The Highland army set off for London, but there was no help, as promised, from France. Although the current Hanoverian dullard, George II, had actually packed treasure chests in case he had to flee back to Hanover, there was no need. By the time the Prince reached Derby, still 100 miles from London, his men were running out of money, supplies, and – crucially – morale.

George II’s forces were massing, assisted by the Campbells, by then the most powerful clan, who remained loyal to the Hanoverians. The Prince’s men won further battle honours, but faced an inexorable onslaught of superior forces, led by the Duke of Cumberland. This culminated in one final bloody hour, at Culloden, when the old Highland system went down to defeat. Vengeance followed. After the battle, wounded Highlanders were slain and relentless persecution was inflicted on the Bonny Prince’s followers. It was not only Jacobites who referred to the English commander as “Butcher Cumberland”. The romantic hero’s cause was lost for ever. All he could do was flee, and await a vessel to return him to exile in France. But the heroine now took centre stage. Flora Macdonald, descended from the chiefly line of the Macdonalds of Clanranald, had shown no more than a tepid Jacobitism – until she was persuaded to help the Prince escape, in disguise as a maidservant called “Betty Birke”.

Fraser’s book describes Flora’s efforts, and it is as pacy as a thriller. She had to help the Prince to elude Hanoverian troops and a significant number of warships. It was decreed that anyone aiding or abetting the Prince would face execution and, to compound matters, there was a £30,000 bounty on his head – the equivalent to £5 million in today’s money. Against all the odds she succeeded, but her own role was ultimately uncovered, and she was arrested. Unlike most Highlanders, Miss Macdonald then had a stroke of luck. Although she could have been charged with treason, her captor, a Major-General and a Campbell, had no wish to take extreme measures. Describing her as a “very pretty young rebel”, he ensured that she had an easy journey to London and a comfortable captivity.

In all this, she became an important transitional figure. In many Whig and Lowland Scots circles, the Highlanders had been regarded as a pestilential nuisance, to be treated like human vermin. But in the years after Culloden, that changed. Once the Highlanders had ceased to be a military threat, they could be romanticised, and

brave, beautiful Flora Macdonald was part of that process. In London and Edinburgh, she was adopted by society. Fame followed. Instead, however, she chose to return to the Long Island, and marry a local laird: Alan Macdonald of Kingsburgh.

This might have led to a happy and prosperous old age. Alas, not so. Her husband was an incompetent farmer and a worse businessman. It may be that he felt the need to prove himself, feeling overshadowed by his wife. Whatever the explanation, any efforts he made only impoverished his family.

In 1774 solution seemed to offer itself in the shape of America, offering cheap land and abundant opportunities. The couple chose North Carolina. But a sad irony ensued as Flora and her husband took the British side during the American War of Independence. He suffered captivity and they both lost all their assets. The colonists were not nearly as merciful as the Hanoverians has been, at least to Flora. She returned to the Long island in 1779, and eked out a living until her death in 1790. But posterity offered consolations, albeit posthumous.

Just before her disastrous foray to America, Dr Johnson visited her, and was charmed, as everyone always was. He celebrated his meeting in prose that would serve as her obituary: “a name that will be mentioned in history, and if courage and fidelity be virtues, mentioned with honour”.

“Pretty Young Rebel: The Life of Flora Macdonald” by Flora Fraser is published by Bloomsbury