Hard Rock, Soft Power: Nobody Does It Better

Our greatest export of the 20th and 21st centuries must be popular music, says Jonathan Wingate

By Jonathan Wingate

October 8 2024

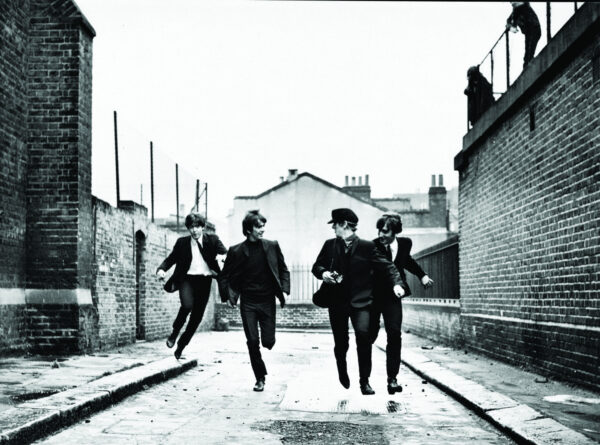

Half a century ago, Mott The Hoople released a timeless song called ‘The Golden Age Of Rock ‘n’ Roll’, but is it possible to really pinpoint its peak? After the meteoric rise of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, British music was sold back to the Americans on a massive scale, a remarkable volte-face which at the start of the Sixties seemed about as likely as finding life on Mars. The fact that America and Britain share a common language is a hugely significant factor in modern musical history, although this still wasn’t going to fool anyone into mistaking Cliff Richard for Elvis Presley. For a new generation of British teenagers who had grown up believing the biggest thrill they could expect was a bottle of fizzy pop, a slow dance, and a polite peck on the cheek, raucous rock’n’rollers like Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Chuck Berry were an electrifying, exotic shock to the system. As John Lennon famously noted: “Before Elvis, there was nothing.” Given that the US population is about f ive times bigger than ours, there is no doubt that when it comes to music, we have been punching well above our weight ever since The Beatles kicked down the door. True originators in what many considered to be a derivative artform, The Beatles smashed through the status quo barrier of the early Sixties, giving kids in America their first excuse for real mania since Elvis had burst into the spotlight in all his hip-shaking, lip-curling glory.

If Mick Jagger and Keith Richards didn’t already exist, rock’n’roll would have had to invent them. Whereas The Beatles emerged smiling together in their bespoke Dougie Millings suits, The Rolling Stones were a surly-looking gang who rejected showbiz convention by dressing the same on stage as they did at home, a move that was every bit as cool as the fuzztone buzz of ‘(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction’. Whilst we produced numerous artists who ruled the airwaves on both sides of the pond, a long list of legendary bands that goes from T Rex and Roxy Music all the way through to The Jam and Blur found it impossible to gain any kind of firm foothold in the American market. Sharing the same language meant that we could repurpose it and inject it with our own slang and songwriting traditions. Initially, our homegrown artists sang about Chevys and Route 66 in fake American accents, but by the late-Sixties, British bands were writing evocatively about Strawberry Fields, Penny Lane and Waterloo Sunset. English cities like Liverpool, London, and Manchester stirred the imagination just as much as the magical imagery associated with rock’n’roll’s mythical meccas such as Memphis, New York, or New Orleans.

Americans have always been far more demonstrative than us emotionally repressed Brits. Our inhibitions combined with an ever-present sense of tension generated by our class system whip up a storm of resentment and rage on timeless classics like The Who’s ‘My Generation’, the Sex Pistols’ ‘God Save The Queen’ or ‘Ghost Town’ by The Specials. The Beatles and The Stones had single-handedly invented the idea of the group as a gang, yet by the time the music business had gone into commercial overdrive in the Eighties with the domination of stars such as Madonna, Whitney Houston, and Michael Jackson, bands had been largely usurped by solo artists, a concept that was perhaps perfectly suited to American individualism.

On this side of the Atlantic, there always seemed to be a far greater acceptance of eccentricity, a willingness to take artistic risks and dive into uncharted territory, which partly accounts for our unique position on the musical map: “If you feel safe in the area that you’re working in, you’re not working in the right area,” explained David Bowie back in 1997. “Go a little out of your depth, and when you don’t feel that your feet are quite touching the bottom, you’re just about in the right place to do something exciting.” The golden age of pop ended with the passing of physical product and the arrival of the internet, which immediately destroyed much of the ineffable mystique that had always been such a vital component of modern music’s enduring appeal to the masses. We may no longer rule the airwaves in quite the same way we once did, but at the peak of its powers, nothing shone brighter than British pop. As Noël Coward observed in his iconic 1930 comedy, Private Lives: “Extraordinary how potent cheap music is.”