Winston Churchill: Destiny’s Child

Despite his share of failures, Bruce Anderson reminds us that the stars aligned to ensure the wartime leader's legacy of greatness

By Bruce Anderson

October 8 2024

Early in the Second World War, Churchill was spending a typical evening with his entourage. The brandy was flowing, as was the talk, much of it from him. Although 20 years younger than the great host, Harold Macmillan, by then a junior minister, was beginning to flag somewhat. “What’s the matter, Harold?” Churchill asked. “Don’t you want to sit up with me and help denounce Hitler?” “But I’m not sure that either of us should be denouncing Hitler,” Macmillan replied. “After all, he made you Prime Minister of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and me a Parliamentary Secretary. No other power on earth could have accomplished that.” A momentary growling frown spread across the PM’s features before being instantly replaced by a glorious, almost beatific smile. “There ish shomething in what you shay.” So there was. Churchill had always believed that he was a man of destiny. Hitler proved him right. In 1940, Britain stood alone. So did Churchill. After the fall of France, on any rational calculation, the UK should have negotiated the best possible deal with Germany, and humiliation seemed to be the price we would have to pay for a sort of survival. Fortunately for this country and for all mankind, Churchill was not interested in rational calculation, still less in humiliation. The eventual victory was his, and Britain’s, finest hour.

Yet even if there had been no war, Churchill would have gone down in history as an extraordinary figure: not quite a world-historical paladin, but one of the most interesting characters of the last century. From the outset, the omens for glory were good. He was a descendant of John Churchill, the first Duke of Marlborough, a great soldier and a formidable political general. Blenheim Palace, the Duke’s family seat, provided a magnificent, and appropriate, location for Churchill’s nativity, while Churchill’s mother was visiting when labour pains came on prematurely. Churchill’s father, Randolph, appeared to have every political gift — brains, oratory, wit, platform presence: this was an inspirational figure who seemed destined for greatness; indeed, effortless greatness. But he turned out to be a charismatic narcissist, whose political career — he became Chancellor of the Exchequer — ended in failure, while his later life was dogged by sadness and syphilis. He and his American wife paid little attention to Winston, who received most love in his childhood from his nanny, whom he called ‘Woom’. What would a Freudian make of that?

“Asquith, Arthur Balfour and Lloyd George enjoyed his wit, took pleasure in his company, and respected his force of mind”

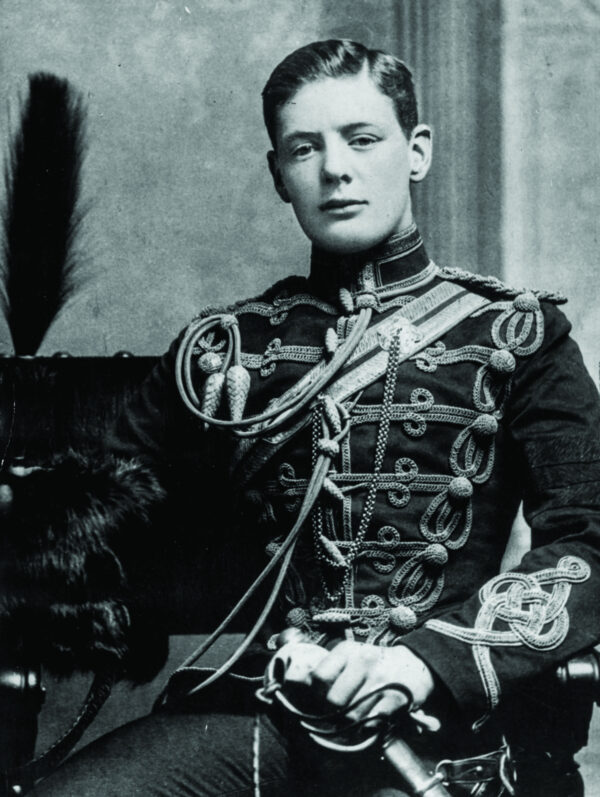

Sent to Harrow, Winston was more successful than the myths suggest. He was especially good at English. But he appeared to have no aptitude for the classics or maths, which was mostly what counted back then. He did seem to have a passion for toy soldiers, so Randolph decided that he should go into the Army. Before his 26th birthday, he had seen action in India, Sudan, and South Africa, where as a prisoner of war, he managed a notorious escape that brought him the early fame that no doubt spurred him to write four books, and unsuccessfully fought a by-election as the Tory candidate for Oldham. He then defected to the Liberals over free trade versus protectionism, an issue that bedevilled politics and broke parties for 90 years. Sound familiar?

As a 26th birthday present to himself, Winston won his first Parliamentary seat. That was closely followed by his first ministerial post. By now, he was already a world famous figure. His qualities had already been identified. He had a formidable capacity for hard work, plus complete intellectual self-confidence, as well as being a commanding speaker. But others proclaimed his defects. There were complaints that he talked too much, took little interest in anyone else’s views, and could not tell the difference between a conversation and a monologue. His table-talk regularly left lesser figures bruised. Fortunately for him, greater men — Asquith, Arthur Balfour and Lloyd George — enjoyed his wit, took pleasure in his company, and respected his force of mind.

He also displayed a breadth of political interests. Before the First World War, he gave almost as much attention to social welfare policy as to military matters. In such matters, he declared himself to be a Bismarckian. He believed that the state should use its power to elevate the condition of the people. Not yet 40 by the outbreak of the First World War, there appeared to be no limit to his ambitions — nor any reason to limit them. Yet this war did him serious damage. In South Africa, he witnessed the consequences of infantry attacking entrenched positions over open ground. There was slaughter, even though the Boers did not have many machine guns. So from the outset — until the tank, for which he was a great enthusiast — Churchill was in search of flanking operations, to avoid the bloody futility of hundreds of thousands of men chewing barbed wire in Flanders.

Hence Gallipoli. Churchill believed that if Britain could force a way through the Straits, Turkey would collapse. Romania and Bulgaria would have joined the Allies and it would have been easier to reinforce Russia. In the view of most historians, this strategic vision was far too optimistic. Moreover, the admirals and generals dispatched to Gallipoli were cautious characters and so a démarche intended to relieve stalemate on the Western Front merely created a new stalemate on the Turkish one. Gallipoli failed and Churchill’s reputation suffered. Many people were ready to believe that he was impetuous and reckless. Gallipoli seemed to confirm that judgment. So did later events. Just after the First World War ended, Churchill wanted a massive military intervention against the Russian Bolsheviks. While this might indeed have been in Russia’s interests, Britain was war weary. The troops wanted to come home. If they had been told to prepare to march on Moscow, it is more likely that there would have been a Bolshevik uprising in Britain.

“As Chancellor of the Exchequer, he took Britain back on to the gold standard and was blamed for the Great Depression”

Then, in 1924, and now reunited with the Tories, Churchill’s political powers led Baldwin to make him Chancellor of the Exchequer. As such, he took Britain back onto the gold standard and was later blamed for contributing to the Great Depression. This is unfair. From the beginning, he had doubts, declaring that “I would rather see Finance less proud and Industry more content”. But the whole weight of official opinion was against him. Almost everyone was a goldbug. If he had resisted the pro-gold pressure, his only supporters would have been McKenna, a former Liberal Chancellor who had never been close to him, and Keynes, who was still some years away from being hailed as the great economic panjandrum and was regarded then more as a gadfly.

Posterity has been reluctant to acknowledge Churchill’s economic prescience. Posterity is wrong. But there were genuine errors. The first was over India, where Churchill refused to recognise the need for moves towards self-government and, in doing so, alienated a lot of potential allies. Then came the Abdication. Anyone who believes in divine providence might thank God for Mrs Simpson. Edward VIII was simply unsuited to be a monarch, especially during a war. Churchill’s insensate support for him convinced many Tory MPs that his day, however stupendous, was now over. This view was confirmed by his drinking and by his choice of friends. A sipper, not a sozzler, he was rarely drunk, but nor was he conspicuously sober. He also seemed to associate with less-than sterling characters such as Bob Boothby, Brendan Bracken and Max Beaverbrook, while a number of MPs who shared Churchill’s disapproval of appeasement felt that his advocacy did not help their cause. All this explains why Robert Rhodes James’s excellent volume on Churchill’s career up until 1939 was entitled Churchill: A Study In Failure. Around that time, Baldwin gave his verdict on Churchill: “Around his cradle, the fairies gave him a cornucopia of gifts — wit, imagination, industry, ability. But one fairy insisted on correcting the balance: she deprived him of judgment and wisdom. So although the Commons enjoys listening to him, it does not take him seriously.” Baldwin was not alone in that assessment.

Left: with the Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII) in 1919; top right: with Roosevelt in 1941; bottom right: with Air Chief Marshall Sir Arthur Tedder in North Africa in 1942.

Three years later, Britain was alone, confronting the abyss. Roosevelt was well disposed, but a lot of Americans were isolationists. We had no allies on the continent. We were short of materiel and the air war was imminent. Yet on one battlefront, there were no grounds for gloom. Lacking everything else, we had a leader who could mobilise the English language and send it into battle. The Battle of France was lost. In the Battle of Britain, there would be no easy victory. But in the Battle of Morale, we had the right commander. Winston Churchill’s birth was probably the most fortunate day in our history. The Empire, high aristocratic politics: the world that created Churchill has vanished and it is hard to believe that such a tempestuous figure could flourish in today’s diminished political environment. Yet, perhaps that is just as well. Churchill was a failure until he became a resounding success, saving his country when no lesser figure would have prevailed: confronting tragedy, fighting through to triumph. It may be that will we not see his like again. If so, we can only hope that we will never have a similar existential crisis, and never need another Winston Churchill.

Event Highlights

Discover what's going on at our locations